Alphaville is 50: After Modernism Lost it Meaning, it Still had its Looks

/In 1965, ahead of its release, French New Wave director Jean-Luc Godard planned on calling Alphaville, his ultra-pulpy sci-fi noir, Tarzan vs. IBM. It’s the story of a thuggish secret agent sent to destabilize a totalitarian regime run by a hyper-rational computer. Alpha 60, the machine running the state bureaucracy, has sanded down any display of genuine human emotion and warmth into a smooth steel slab of commodified and mechanized robotic efficiency. That’s the IBM part. The Tarzan part is Lemmy Caution, the self-actualized detective fisticuffing his way through endless machine bureaucracies. It’s a prototypical Cold War dystopia in many ways, equally concerned about the rise of totalitarianism and computer technology, and how they might work together.

In fact, a better title would probably have been Tarzan vs. Corbusier, because Alphaville is about the anxieties surrounding the spread of Modern architecture as much as it’s about anything else. Alpha 60 is essentially the meanest and least humanistic manifestation of Tom Wolfe’s White Princes in From Bauhaus to Our House; (one section that would have made Wolfe smile: Caution discovers one staunchly anti-bourgeois mass execution method where dissidents are invited to a concert hall and electrocuted in their chairs, rows of theater seats flipping over to deposit bodies into garbage bins). Similar to Modernism, Alpha 60’s unquestioned proclamations that society must work like ants to perpetuate mechanized order are presented as logical, inevitable, and for the universal good. These proclamations are often made directly to the viewer, through mechanized, croaking voiceover narration (delivered by a voice actor with a mechanical voice box) that lends an air of sinister omnipresence to Alphaville. Through a combination of 1984-style surveillance and Brave New World commodification and pacification, Alpha 60 has eradicated emotion, art, and nearly all culture. The only thing remaining is the apparatus to perpetuate its own expansion; intimidating enough to inspire the “Outer Countries” to send secret agent Caution (played by American-born actor Eddie Constantine) to destroy it, and abduct its inventor, Professor Von Braun (Howard Vernon).

Translated into architecture, Alpha 60’s world contains all manner of recognizable Modernist tropes: long smooth, frictionless halls of travertine. Endless, repetitive building facades. Expansive, uninterrupted floor plans. Rational, logical, inevitable. And horrific. We’re treated to several public executions, and threatened with a fate worse than Cold War atomic annihilation. Early Modernists said ornament was a crime. In Alphaville, any thought, action, or reaction that does not further the aims of the state is a crime.

Fifty years old this year (and set for a remake by Twin Peak cinematographer Frank Byers), Alphaville shows Modernism at a critical point before it became co-opted as yet another swatch in high-end designers’ color palette. Pick up the latest issue of Dwell. Cruise the Internet for Mad Men-inspired furniture. Fifty years ago, some pretty smart, influential people thought this stuff was going to help ruin the world. And if you look closely at Alphaville, the clues that this was never going to happen were already hidden in plain view.

- - -

Most science fiction dystopias use custom-made sets to communicate an aesthetically consistent, fantastical and disturbing new reality (Blade Runner, Metropolis, Brazil). But Alphaville was more interested in deriving confusion and anonymity from already-existing places. Establishing shots are rare, and Godard uses abstract imagery, like flashing lights partially cut out of frame, to signal psychological dead ends and spatial breaks. Alan Woolfolk’s essay “Disenchantment and Rebellion in Alphaville,” explains that Alphaville is a rat’s nest of transitory zones: corridors, lobbies, and stairs, all powered by an unaccountable bureaucracy. It even throws our protagonist Caution off his game. When asked what he thinks of Alphaville, he says, “It’s not bad, if I knew where I was. . .” The film is defined by the denial of spatial understanding, not any grand stroke of world-creation.

This excruciatingly banal funhouse maze was not dreamed up in a studio back lot. Godard shot the movie in existing buildings built in the 50s and 60 in Paris, including (according to Woolfolk) the Maison de ‘lORTF and the Esso Tower in La Defense, the mega-scaled Modernist high rise district on the city’s outskirts, culturally and geographically the closest thing to Godard’s Alphaville in existence. True to the still-active Godard’s legacy, Alphaville is an incredibly rich, aesthetic pleasure; nearly every shot a gallery-worthy composition of neo-film noir paranoia and freewheeling bravado. But the film’s most audacious trick is making Paris look like downtown Des Moines. It studiously avoids any of the city’s eminent cultural propriety, and focuses on only the poorest-aging and most anonymous, alienating corporate Modernism, fit for a regional bank headquarters in any number of C-grade American downtowns. Indeed, the Esso Tower was demolished in 1993. It was only 30 years old.

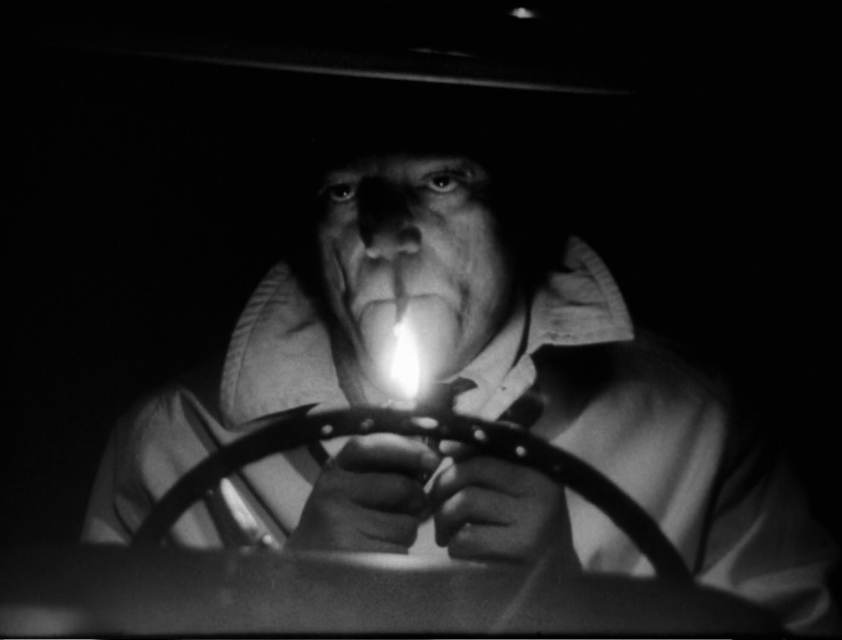

The film begins as Lemmy Caution, posing as a journalist, infiltrates Alphaville, on a mission to abduct Professor Von Braun and destroy Alpha 60. Caution is a man of action, hard-boiled, and trench-coat clad. His face is often only illuminated by the spark of a cigarette lighter, casting shadows that accentuate wrinkles and scars. His own appearance is out of step with the polished and exacting world around him. He shoots his gun without aiming. His favorite phrase is a barked “Clear out!” His go-to move when things get rough is to put his hands around the neck of a woman he’s being wooed by and threaten them. It always seems to work. Before killing Von Braun, he quips, “Yes, I’m afraid of death, but for a humble secret agent like me, it’s an everyday thing, like whiskey. And I’ve been drinking all my life.” He’s a campy pastiche of James Bond, Dick Tracy, and any number of smoldering film noir leading men who harbor a terrible secret but need you to believe they can still love. Decrying the lack of heroic leading men to depose Alpha 60, Caution even asks, “Is Dick Tracy dead? What about Flash Gordon?” In fact, American-born actor Eddie Constantine was mostly sending up himself. He played FBI agent Lemmy Caution in seven French films before Alphaville.

Early on, Caution is checked into a hotel room by a state-sponsored “level 3 seductress,” complete with a serial number tattoo on her back. He proves his macho credentials to her by rebuffing her advances, with a quick, “Look sweetie, I’m big enough to find my own ladies. Clear off now.” After a mysterious gunman attacks him, he suspects the seductress is in on it, and he tells her to sit on a chair and hold a pin-up nude over her head. He lounges on the bed, opens a book, and takes two no-look shots with his handgun, one through each breast of the pin-up. Early on, it’s established that women are mostly static objects, used for target practice, or sexualized sculpture.

Later, Caution meets with former colleague Henry Dickson (Akim Tamiroff) who was previously dispatched on the very same mission. Dickson, now a degenerate alcoholic, is holed up in a flophouse hotel, where guests (mostly dissidents who don’t fit into Alpha 60’s degraded mold of humanity) are actively encouraged to kill themselves. His failure to complete his mission or adapt to this society of “termites” and “ants” Alpha 60 has created dooms him. He’s surrounded by dingy, rotting Victorian wallpaper, a signal that this is a place old and outmoded things go to die. And he does, during a sexual encounter with another government-issue prostitute, as Caution hides in the corner and takes pictures.

Caution eventually connects with Professor Von Braun’s daughter Natacha (Anna Karina), who genre conventions force to fall in love with him, even though he’s constantly grabbing her by the neck and putting her life in danger. With her, he attends what she distractedly describes as a “light and sound thing,” which is really a mass execution with performative elements that put it among the long list of dystopias that predict the rise of reality TV. This section of the film also offers its only presentation of grand, monumental Modernist space. Inside an expansive natatorium that could double as a bomb bunker, Lemmy and Natasha see a long line of men leading to a diving board. Synchronized swimmers in matching swimsuits stand at the ready. The men are walked to edge of diving board, and peppered with machine gun fire. From the observation gallery above, there’s polite clapping, and one of the attending dignitaries (including Professor Von Braun) explains that they are being executed for “behaving illogically.” (One man cried after his wife died.) The synchronized swimmers dive in to retrieve the bodies, starting with a few thrusts of a knife in case any are still alive, and ending with a few underwater flips and handstands. Godard’s camera hovers above them all, an expanse of water churning with death and oppression between the black-clad executioners and the white-shirted condemned. Thematically, Alpahville is a rather typical sci-fi dystopia for its era, engaging in hoary sci-fi conceits (like an evil computer short circuited by being asked to contemplate love and poetry). But the ball gowns worn by the mass execution attendees and refreshments offered in the lobby point to reality TVs ability to make our most base voyeuristic desires appointment viewing. Of course, the level of spectacle is all wrong. This is public execution as effete opera, not bawdy and populist television. Having never seen a single “Real Housewife” hurl champagne at a frenemy or Bad Girls hair-pulling tornado, he couched this prescient pop-culture evolution in an already outmoded art form.

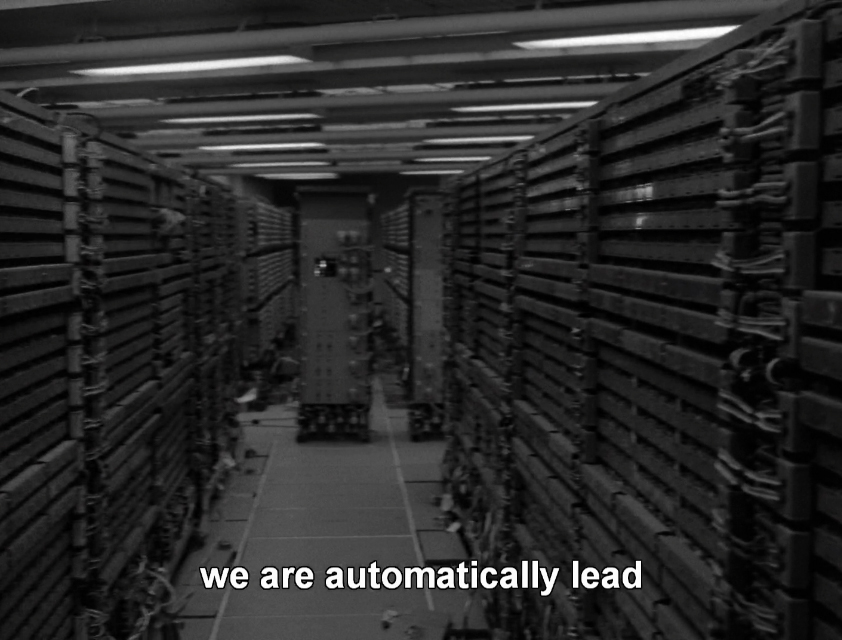

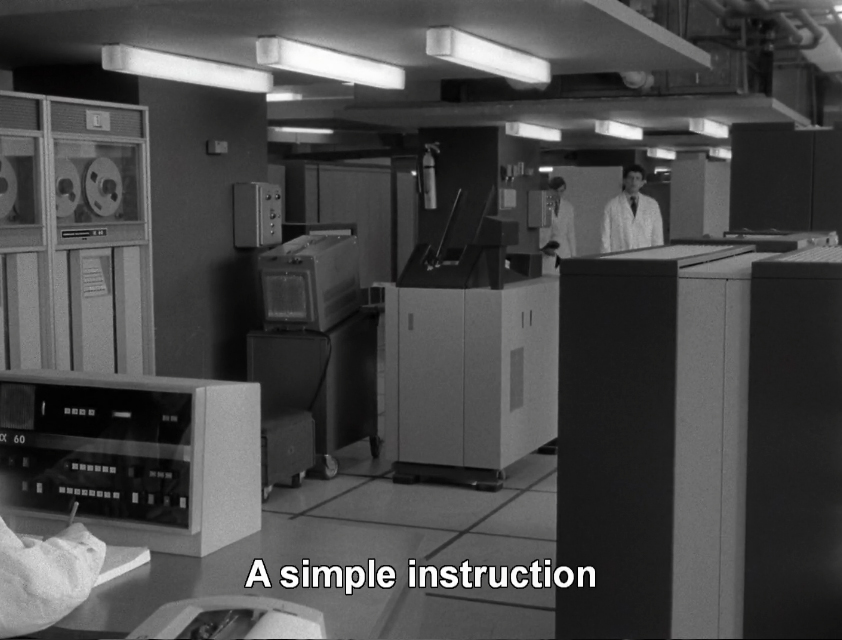

It’s a horrific tableau, surrounded by a movie full of fallout-shelter laboratories, computer console mazes, and seizure-inducing media screens. But even as Godard dunks viewers in a sensory deprivation tank as designed by Kevin Roche, he offers clues that his feelings about these austere, Modern spaces are more complex. While Natacha slowly, luxuriously descends a floating, freestanding spiral staircase, the camera orbits around it, meeting her at the ground floor, where she meets up with Caution. As the duo heads towards the exit, the camera pin-wheels around the duo, relishing the open floor plan, showing off the column-free expanses, and generally behaving like a real estate promo video. Later, when Caution explores Alpha 60’s computerized innards, a shot explodes into a riot of rectangles; light fixtures, desks, computer consoles, and mainframes, an almost Cubist sculptural array of forms.

Godard is being won over by the stylish brand of minimalism these spaces offer, even as he decries them. If so, he’s not the only one being tempted. As Caution finally confronts Von Braun and makes his intentions clear, Von Braun offers him a deal: Join Alphaville, and become a double agent. Spy on the “Outer Countries,” and aid us in our preemptive war against them. For your services, you get “control of another galaxy,” “You’ll have gold. “You’ll have women,” Von Braun says. Caution demurs, shooting Von Braun, which sends everyone in Alphaville into a fit of full-body convulsions. He won’t be co-opted.

But Godard’s revelatory minimalist mise-en-scene flourishes give a clue that Modern architecture definitely, definitely will be. Caution won’t sell out, but Modernism will be defanged and flat-packed into Toyota Camry trunk-sized boxes, stacked to the sky in suburban IKEAs. It’s just too attractive not to be.

- - -

Whether you ask Godard’s Alphaville or the manifesto-smiths at the Bauhaus, Modernism was always a tool for throwing away that past and rebuilding society. The two differ only in what was to be built: an apocalyptically mutilated humanity, or a socialist workers paradise. (In fact, the gap between these two ambitions was the entire theme of French pavilion at the 2014 Venice Biennale.) When nothing of this sort occurred, most of what was left was the aesthetics, and Modernism became a consumer sensibility.

This was well under way by mid 60s when Philip Johnson’s MoMA show was 30 years in the rearview mirror, its anti-bourgeois import overshadowed by a great many new shiny corporate headquarters all designed in the tradition of socialist workers housing. Beyond the city, throwing out the history books was a tough sell. Vast new suburbs of puffy, gable roofed Neo Neo Tudor Colonial Mission mutants marched across the land. Almost no one built workers paradises, and when they did there were those damn Art Deco curlicues. Or, they were mega-scaled Corbusier-styled Radiant Cities infected with any and all social pathologies that would be dynamited in a few short years with such force as to destroy Modernism itself. (Auspiciously, Alphaville was released the year Corbusier died.) Philip Johnson’s Glass House is an incredible aesthetic statement, but for 65 years it’s been essentially unable to say anything to the vast segment of society who doesn’t automatically know who David Remnick is. If a resident of Alphaville wanted to take a North American tour of successful neighborhood-scaled Modernism, you could take them to Mies’ Lafayette Park, drive them around for five minutes, and credibly tell them the tour is over. Modernism apparently was not for revolution. So what was it for? Maybe its just for fancy dinner parties where the museum curator brings the polenta, the critic brings the quail, the flavor-of-the-month conceptual artist brings the arugula and beet salad, and the architect forgets the wine and only shows up with commiserations that no one takes Modern architecture seriously anymore. (And for transparency’s sake, here’s how I butter my bread for this sad gathering: I detest anything new made to look old and find it beyond depressing that I was six and living in rural Iowa during the MoMA Deconstructivist Architecture show. Modernism is awesome, my favorite buildings make me feel like a super villain, and I get that this is an unpopular opinion.)

Modernism is a way to divide your houzz.com search, a way to signal going to good schools and reading the right websites. It's a flavor of moneyed good taste. Its aspirations still seem pretty pure-hearted, if not comically naive, and many of its good ideas are still intact, though they’ve been more effectively endorsed by other philosophies. (Its preference for density and modularity is echoed in the newer sustainability movement, for example.) But it’s an aesthetic, not an inevitable way of life.

Alphaville is the moment before this recognition settled over the land. In it, Modernism still had teeth, and was potent visual symbol for technology-driven totalitarian efficiency that remakes society in its own image.

Another thing Alphaville gets wrong is the form lowest-common denominator, machine-designed building will take. Godard thought that mechanized efficiency would bring about cheap and omnipresent Modernism in all sectors of building. Endless rectangular molds to pour the thin remaining gruel of humanity into. But the opposite is true. All those cheap suburban manses and their plastic pediments are churned out from a CAD template and maybe given a cursory glance by a human. But pay millions for four glass walls wrapped around a rectangular floor and roof, and you have to listen to a man in funny glasses expound upon his vision of the true “nature of space.” In the world outside of Alphaville, robots (like Alpha 60) do gabbled roofs. Auteurs (like Godard) wearing berets and capes do flat roofs. In our world, Modernist architecture is an art-object, which would have been eradicated in Alphaville. That’s the central contradiction of the movie. Despite its minimalist austerity and sometimes arcane philosophy, Modernism has always been fully in creative human hands, which makes it suspect from the point of view of totalitarian masters, and a humanistic aspiration for everyone else.

Zach Mortice is a freelance architectural journalist living in Chicago. He has written for Architectural Record, Metropolis, Architect Magazine, and Landscape Architecture Magazine. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram.